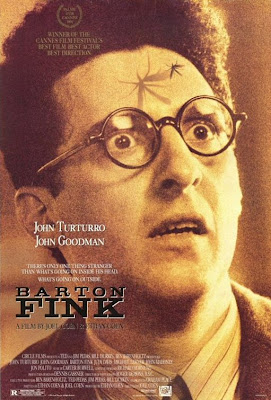

Barton Fink (John Turturro) wants to write a play about the working man, the guy in the streets; he voices exasperation with the fragmentary conception he has from the intellectual’s removed balcony of experience and background. How does one who never travels in such circles begin to write a comprehensive or progressive portrait of a working man based on “shopworn abstractions about drama” as Barton puts it when laying bare all these tormenting doubts that have left the paper in his typewriter with nothing, nothing but a few sentences:

FADE IN

A tenement building on Manhattan’s

Lower East Side. Early morning traffic

is audible, as is the cry of the

fishmongers.

The man who bears witness to Barton’s troubled confessional is Charlie Meadows (John Goodman) a genial traveling salesman who happens to reside on the same floor of the Hotel Earle where Barton is staying during a transitional period while trying his hand at screenwriting for the movin’ pictchas. Barton is a neurotic poindexter, highly intelligent, but devastatingly unconscious of the fact that all of the doubts, reservations, and discouragement he goes on and on about, ever preoccupied with his own thoughts of artistic inadequacy trampling his agitated screed all over Charlie’s replies, would be solved if he only listened to Charlie’s aborted attempts to join the conversation. Charlie is the very type of common man he so desperately wants to understand. Charlie barely ever gets a word in.

Barton Fink is, in many ways, as much of an agitated admission from the Coen Brothers as it is from the titular Fink: it is at once a mission statement, an artistic crossroads, and a resignation: Barton has good intentions, and his sequestered intellect has produced an idealized portrait of the working class, the noble savages, the dignified downtrodden, the real heroes as he sees it. His conception of the common man is as rosy and idealized as the painting of the woman gazing out at the ocean that hangs insinuatingly on the wall in his hotel room. By the end of the film, he will have experienced a shattering of this conception, and even the hotel itself rebels at his deluded conception – the walls the painting hangs on drips and the wallpaper peels, obstinate in its refusal to stick, even after Barton has gone to lengths to push it back against the sticky substance that seems to be sweating from the Hotel walls.

The Hotel is a living organism, perhaps a symbolic incarnation of Barton’s mind, but more likely a depiction of the human body in all its naked corruption.

The first night in the hotel, Barton’s face is descended upon by a mosquito, leaving a buzzing swollen mark where he has been fed upon/drained. One of the posters for the film depicts the mosquito prominently. What does the mosquito mean? What does any of it mean? This is one of the most secretive and brilliant films of the 90s, and never wants for contemplation. Pondering it is a rich and endlessly rewarding pleasure for me. It is my very favorite of favorite Coen films.

I don’t presume to know exactly what everything means, but I believe at the heart of the film is a pessimistic realization that the noble savage may just be a savage, the seemingly too obvious conclusion that living low is just as capable, perhaps more so, of producing irredeemable, base individuals. This is the same thought that struck me while watching Lars Von Trier’s Dogville – the fearless and potentially offending proposal that the conception of the dignified working class that so many patronizing liberals hold, is flat out naïveté. Pity for a starving dog clouds the truth that the dog is, indeed, starving, and such neglect and maltreatment inspires nasty, selfish, even violent behavior. The mangy cur is something that invites solicitous affection until its mistreatment sinks its fangs into your hand.

If you haven't seen Barton Fink, I'd strongly recommend not continuing.

As we learn to chilling ends late in Barton Fink, our lovable sad-sack Charlie is a sex-starved monster, who exploits his transient occupation as a means of gaining entry to homes and murdering scornful housewives.

Charlie: Jesus, what a day I had. You ever had one of those days?

Barton: Yeah. Seems like nothing but lately.

Charlie: Jesus, what a day. Felt like I couldn’t have sold ice water in the Sahara. Okay. So you don’t want insurance. Okay. So that’s your loss. But, God, people can be rude. Feel like I have to talk to a normal person like you just to restore a little of my…

Barton: No, it’s my pleasure. I could use a little lift myself.

Charlie: Good thing they bottle it, huh, pal? (pauses to take a swig from flask) Did I say rude? People can be goddamn cruel, especially some of these housewives. Okay. So I have a weight problem. That’s my cross to bear. I don’t know.

Barton: It’s a defense mechanism.

Charlie: (angry) Defense against what, insurance? Something they need? Something they should be grateful to me for offering? (calms) A little peace of mind.

On Barton’s second night in the Earle, a disturbing thing happens: he hears, through the thin walls, something that, at first, sounds like laughter. Mad, insane laughter. It isn’t laughter. It is the sound of a man sobbing. Barton calls down to the front desk to complain. He hears the phone ring through the wall, muffled conversation, and then heavy footsteps which sound purposefully to his door, followed by a loud knock. Turns out it’s Charlie. He is a big affable man, and his wide grin only hints at the cracked personality beneath on repeat viewings.

Charlie: Those two lovebirds next door driving you nuts?

Barton: How do you know about that?

Charlie: Know about it? I can practically see how they’re doing it. Brother, I wish I had a piece of that. Seems like I hear everything that goes on in this dump (pressing fingers against his ears and wincing in pain) – pipes or something.

His mild irritation at the wall-penetrating sounds of passion from the Hotel Earle’s resident “lovebirds” conceals a raging resentment, a dark sadness that gives way to psychotic vengeance. On his third night at the Earle, Barton hears through the walls sounds of sex, a woman moaning. Shortly thereafter, he hears it again, mingling with the muffled moans, the disquieting sobs of someone deeply distressed coming from the opposite wall. No doubt this is Charlie. You take a guess at the reasons for his crying.

Barton Fink: An Appreciation, Part 2

No comments:

Post a Comment