“Barton,

May this little entertainment direct you during your sojourn among the philistines.

Bill”

Of the two major plot threads in Barton Fink, one being the Earle’s dark night of the soul, the other is not quite as overtly sinister: it details Barton’s seduction at the hands of a bombastic movie producer (Michael Lerner, delivering Coen dialogue as if born to) and his relationship with Bill Mayhew (John Mahoney), a once great highbrow writer who has essentially sold his abilities to the picture business. Mayhew, the once great Southern novelist turned screenwriter, is an overt allusion to William Faulkner.

It could also be a combination allusion to Faulkner and F. Scott Fitzgerald, both highly respected novelists who, whether compelled by creative stagnation or financial issues, found themselves in Hollywood whoring their talents writing bread and circuses fluff clearly beneath them. The first time we see Mayhew, he is partially obscured in a bathroom stall, vomiting hideously from a hangover. It is no coincidence that Barton's introduction to the man is in a bathroom, and the first thing Mayhew does after washing his hands at the sink and composing himself is to retrieve a flask from his waistcoat pocket. As the film moves along, Barton’s reverence for the man diminishes as he sees what the transition from writer to hack has done to him. Mayhew is a bitter drunkard, at first briefly pretending to be proud of his work for the movie industry, but before long, voicing hateful remarks, and autographing his latest book, hilariously titled Nebuchadnezzar (a playful nod to Faulkner's Absalom, Absalom?), "Barton: May this little entertainment direct you during your sojourn among the philistines."

It could also be a combination allusion to Faulkner and F. Scott Fitzgerald, both highly respected novelists who, whether compelled by creative stagnation or financial issues, found themselves in Hollywood whoring their talents writing bread and circuses fluff clearly beneath them. The first time we see Mayhew, he is partially obscured in a bathroom stall, vomiting hideously from a hangover. It is no coincidence that Barton's introduction to the man is in a bathroom, and the first thing Mayhew does after washing his hands at the sink and composing himself is to retrieve a flask from his waistcoat pocket. As the film moves along, Barton’s reverence for the man diminishes as he sees what the transition from writer to hack has done to him. Mayhew is a bitter drunkard, at first briefly pretending to be proud of his work for the movie industry, but before long, voicing hateful remarks, and autographing his latest book, hilariously titled Nebuchadnezzar (a playful nod to Faulkner's Absalom, Absalom?), "Barton: May this little entertainment direct you during your sojourn among the philistines." Barton arranges an outdoor luncheon with Mayhew through Mayhew's lady-friend, Audrey (Judy Davis). The afternoon begins calmly enough, but once Bill starts spewing acid and bitterness, the luncheon is cut short. He says writing helps him to escape, and that if he couldn't escape, he'd go mad. Drinking from a bottle of whiskey, he mentions that the bottle helps sometimes too.

Both Audrey and Barton argue the opposite.

Barton: Look, uh, maybe it’s none of my business but don’t you think a man with your talent, that your first obligation is to your gift, shouldn’t you be doing whatever you have to do to work again?

Mayhew: And what would that be, son?

Barton: I don’t know exactly, but I do know what you’re doing with that drink, you’re cutting yourself off from your gift, and from Audrey, and from your fellow man, and from everything your art is about.

Mayhew: Oh, no, son, I’m buildin’ a levee - gulp by gulp, brick by brick – puttin’ up a levee to keep that ragin’ river of manure from lappin’ at my door.

Dismayed and outraged at Mayhew’s hateful behavior, Fink, again, as with his deafness to Charlie, misses the big picture. As I said in Part 1, Barton is at the cusp of a momentous crossroads. He fails to see that Mayhew, who chose his path long ago, has turned into a man who has been wrecked by compromising his own refined sensibilities. How many steps removed from conforming art to the plainer, less cultivated tastes of a wider audience is it to just plain dumbing oneself down? Barton wants to write a picture about a common man for the common man, but he doesn't know what it means to be a common man. Should he tamper with his writing for an audience he doesn’t fully understand or identify with? If not, should he quit? Or be ashamed? Are the Coen Brothers justifying snobbery? What's the difference between being a snob and having refined tastes in film, literature, music, painting, et cetera? Does being dismissive of bad art make one a snob? Does being ignorant and dull in the face of elegance and subtlety demand scorn or even light rebuke? These are important questions with no easy answers, but questions inherent to the creation of art. That is what makes Barton Fink an essential art film, an indispensable contribution to the work of cinema.

After his encounter with Audrey and Bill, we see Barton awakened from slumber by another mosquito. He looks at the typewriter sitting on his desk with dread. Once he sits down, we are afforded a look at his progress, and find, that not only has he made none, it has regressed: Now, instead of “Early morning traffic is audible” the manuscript reads “It is too early for us to hear traffic; later, perhaps, we will.” The “cry of the fishmongers” can still be heard, but “faintly” and the “tenement building on Manhattan’s Lower East Side” is now “A tenement hotel on the Lower East Side.” Sharper viewers than I would notice that the brief allotment of text has changed ever so slightly from before on their very first screening of Barton Fink; here they are, back to back:

FADE IN

A tenement building on Manhattan’s

Lower East Side. Early morning traffic

is audible, as is the cry of the

fishmongers.

FADE IN

A tenement hotel on the Lower East

Side. We can faintly hear the cry

of the fishmongers. It is too early

for us to hear traffic; later,

perhaps, we will.

As Barton looks at his inability to write what he intended with a look of agonized concentration on his face, the camera descends below his desk to where his shoes lay in front of his socked feet. He inserts them into the shoes, and we see that the shoes are too big (they are Charlie’s shoes; he and Barton took each others’ by mistake). His feet in Charlie’s shoes, not fitting, the camera moves back up to Barton as he types: he pauses, staring at what he has written, with a look of utter defeat.

Charlie knocks on his door, and enters holding Barton's shoes. They exchange.

This is the moment where Charlie expresses his frustration with the cruelty of his customers, the first time we witness an angry outburst from the ostensibly sweet-natured man. That's nothing compared to the outburst to come.

The closer Barton comes to his deadline, the crueler his writer's block seems, until, finally, one night, he phones Audrey in desperation. She visits him at the Earle, and reveals a shocking revelation: she wrote Nebuchadnezzar, as well as the rest of Bill's recent work. She offers to assist him, but before long, they have become amorous and as they recede onto the bed, the camera drifts into the bathroom, where their sounds of lovemaking funnel ominously down the drain in the sink and begin a voyage through the plumbing of the Hotel.

The next morning, Barton awakens to a nightmare. Audrey has been murdered during the night and the mattress is soaked in her blood. Shrieking involuntarily, he alarms Charlie, who insists that he let him help. Charlie tells Barton to go about his day as planned, and he will take care of the body. When Barton returns from meeting with the movie producer, the corpse is absent, and Charlie, who a few evenings prior informed Barton that he would be leaving on a short trip this very day, arrives at Barton's room with a parcel wrapped in brown paper and tied with a string. He bids Barton adieu.

The true nature of the noble working man is contained within that parcel, and it is the only thing Barton takes with him from the Hotel Earle, other than his screenplay. The parcel is a grim memento, and it sits next to him on the beach as he stares at a real life recreation of the painting in his room: the beautiful woman in the bathing suit, gazing out, as if to the future, over a gently lapping surf. There is one slight difference though: a seagull. As Barton sits next to the parcel, he watches the seagull crash down into the ocean, abruptly disturbing the tranquility. Art doesn’t reflect life. We don’t need to look inside the parcel to know what’s in it.

A common complaint from detractors of Joel & Ethan Coen is that they sneer at their characters, are contemptuous of them. Upon cursory glance, one might suggest this possibility began with the polite denizens of Brainerd who seem to live and speak in an innocuous state of slow-motion incomprehension. Well, Fargo was their 6th film. In their first film, Blood Simple, you have Ray, played by John Getz. He is a drawling sort of good ol’ boy, not an intellectual by a long shot, but the Coens certainly portray him as more often cunning than not, cleaning up a bloody mess and disposing of a dead body effectively, though with suspenseful inefficiency. Then you have H.I. McDunnough (Nicolas Cage) from Raising Arizona. The Coens keenly milk Cage’s drooping, vapid expression for all its comic potential, while simultaneously making him the mouthpiece for their ornate dialogue. Seeing such grandiloquence from a hayseed produces an absurd incongruity that makes people laugh if they get the joke (Roger Ebert, the point flying twenty or so meters above his head, commented about H.I.'s language: “…that's not what you expect from a two-bit thief who lives in an Arizona trailer park.”). Even if Raising Arizona was meant to be taken seriously (aside from the poetic coda mystically scored by the great Carter Burwell), one could surmise that the Coens respect H.I. enough to reward him with such florid articulacy. There is no issue in Miller’s Crossing, as all the characters are shady inside men running in elite circles, some being more ruthless (and lucky) than others. So it was with Fargo that the Coens first dared to put their caricatures within the framework of a somber tragedy, provoking cries of “Condescension!” and “Contempt!” Barton Fink has caricatures, yes, but the film, being allegory, does not take place in reality, as Fargo claims to do. Fargo, at its outset, purports to be a true story (it is not, as we all know by now) but I think a very good case could be made that it really does not take place in reality, but is more of a fable in the tradition of David Lynch's Blue Velvet. I sincerely doubt that the depiction of the locals are intended as a hateful criticism of real-world Minnesotans. Some of them are portrayed as ignorant of duplicity and scheming (which does not mean they are portrayed as stupid) and some are portrayed as simpletons, but not in a nasty way. Quite the opposite in fact, as the Coens seem to delight in their quaint guilelessness. Fargo, in its tone with the comical asides, seems to suggest that these are people to cautiously admire, or at the very least, be thankful for.

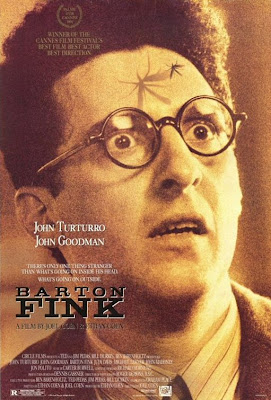

The Coens are nuanced filmmakers, and Barton Fink is a massive turning point in the attitudes and themes of their work. Barton Fink reveals, yes, Barton (John Turturro) is, partially or more so, a representation of the bespectacled, brainy Joel & Ethan, who wrote the screenplay for it, their 4th film, while, you guessed it - struggling with desperate writer’s block over the second half of the screenplay for Miller’s Crossing. Looking at their previous work, and also looking to future work, they sensed a dilemma: there is an unavoidable elitist tendency within them that is troubling, and must be exorcised. What they, and Barton learn, by the end of Barton Fink, is that this part of them cannot be surmounted; it is as much a part of them as their childhoods, as inseparable and natural to them as their personalities, it is what makes them the Coen Brothers – it is something to be embraced, not exorcised. As the Hotel Earle burns, summoning allusions to Dante’s Inferno and the Apocalypse, Barton makes his way out of his room, suitcase in hand, departing for the exit, and I felt like the Coens had finished wrestling with their guilt, moving onto the more widely acclaimed pastures of cocky assurance that is displayed so confidently in Fargo, The Big Lebowski, O, Brother Where Art Thou?, The Man Who Wasn’t There, and No Country For Old Men. They found themselves in Barton Fink, after being baptized in fire.

Grade: A+

Barton Fink: An Appreciation, Part 1